Pureora Forest Park, New Zealand

Pureora Forest Park protects one of the most extensive tracts of pristine native podocarp woodlands on New Zealand’s North Island. Visiting here is like taking a trip back in time to primeval New Zealand.

Step into a fairytale forest filled with giant trees and indigenous birds, including the elusive kōkako. New Zealand’s age-old indigenous forests are part of the country’s natural legacy.

Their giant podocarp trees have endured through the centuries and are at the core of the forest ecosystem. Nevertheless, introduced predators, land developments, and logging have all taken their toll on these woodlands.

Pureora Forest Park was the last of New Zealand’s national parks to be opened up to logging operations. However, in 1946, the government sanctioned timber enterprises in the park, which significantly reduced the number of indigenous podocarp trees.

People took extraordinary measures to protect this tract of virgin land. Here is the story of Pureora Forest Park and why you should visit it.

Protecting Pureora Forest Park

Dave Pye worked as a timber cruiser in Pureora Forest between 1962 and 1978. Logging was challenging work back then — without modern machinery, workers used axes and 2.5-metre saws to fell the trees.

Nevertheless, the high demand for houses — and the materials to build them — in these post-WW2 years drove timber sales sky-high. ‘We would cut down an average of 150 to 170 trees a day — because they were so close together,’ relates Pye.

Conservation agencies and passionate individuals fought hard to preserve the forest. However, the government met peaceful protests and petitions with deaf ears. Matters came to a head in January 1978 when there was a critical stand-off between the loggers and protesters.

Environmental activist Stephen King led the 1978 protest. He describes the first time he visited the forest while compiling a petition against logging of all lowland indigenous woodlands. ‘I was so taken by the majesty of it,’ he says. ‘It is tragic that so many of New Zealand’s homes were built from these trees, and yet so few of these arboreal giants remain.’

After submitting the petition, King and fellow activists compiled a lengthy motivational document and submitted it to Parliament. It detailed the dramatically decreased numbers of rare birds like the kokako due to logging in Pureora. Furthermore, they explained the critical role that these ancient forests play in preserving these endemic species.

They requested that the government urgently stop logging to protect the remnants of this precious ecosystem. ‘When the government failed to respond, we had no choice but to climb the trees,’ says King. ‘From day one, we occupied the forest, so they couldn’t log anywhere in it and be sure they wouldn’t put anyone’s life in danger.’

He tells how his brother sat silently in a treetop one day as loggers felled a 40-metre rimu tree next to him. He didn’t utter a word until the tree had crashed onto the forest floor. When he then alerted the loggers of his presence, they were shocked that he had not called out for them to rescue him during the process. ‘On that day, at that moment, they stopped the logging on safety grounds,’ says King.

»Pureora’s ancient forests are a sanctuary for both nature and the soul.«

Pureora’s special Podocarp forests

Pureora Forest Park’s majestic podocarp trees are magical in and of themselves. There are precious few places on North Island where one can experience such dense collections of these age-old majestic giants. Podocarps belong to a class of southern hemisphere conifers.

Reaching over 50 metres, they form the forest’s emergent layer, with broadleaf trees creating a lower canopy. Ecologists estimate many of Pureora’s podocarp trees to be hundreds of years old and some close to two centuries old. However, the trees are just one striking feature of this ancient ecosystem. Myriad other indigenous species thrive in the forest’s haven and contribute to its exceptional ecosystem.

Pureora’s birdlife is particularly exceptional. The reserve is home to one of New Zealand’s most threatened birds - the kokako, with its distinctive blue or orange mouth wattles. The kōkako belongs to the wattlebird family and has existed solely in New Zealand for centuries. Like many endemic species, kōkako populations were decimated by introduced predators like cats and rats. In many parts of the country, it has disappeared entirely.

In the 1980s and 90s, Pureora’s population declined rapidly, hitting a low of eight breeding pairs in 1995. However, as its custodians learned more about the park’s ecology, they implemented more effective pest control and other conservation strategies. The change in the kōkako population reflected the success of these measures.

The number of breeding pairs increased exponentially over the next few decades. In May 2023, a Department Conservation survey revealed that there are now around 670 breeding pairs in the forest. Similarly, the forest is a sanctuary for the kākā, an endemic parrot at risk of extinction. A long-term monitoring programme shows that these endangered birds are increasing by around 6.4% annually.

Getting around Pureora Forest Park

Hiking

Walking through Pureora Forest is arguably the best way to experience its primeval trees, deep-green mosses, lush ferns, and beautiful birds. You do not have to be an experienced hiker or super-fit to experience the park’s trails.

There are many short and easy routes for those who prefer a gentle meander over a full-day trek. A great family-friendly (and all-fitness-level) option is the Centre of North Island Walk, which takes hikers to the island’s geographical centre. Alter-natively, the one-kilometre Totara Walk covers some of the forest’s oldest and most enormous podocarps.

Another memorable hike is the Pouākani Tōtara Tree Walk, which takes you to the largest tōtara ever recorded. This ancient behemoth has a circumference of almost 12 metres, and scientists estimate it could be close to 1850 years old. The 10-minute Waitara Lagoon Walk transports one to an enchanted world where towering trees reflect on the glassy water.

Biking

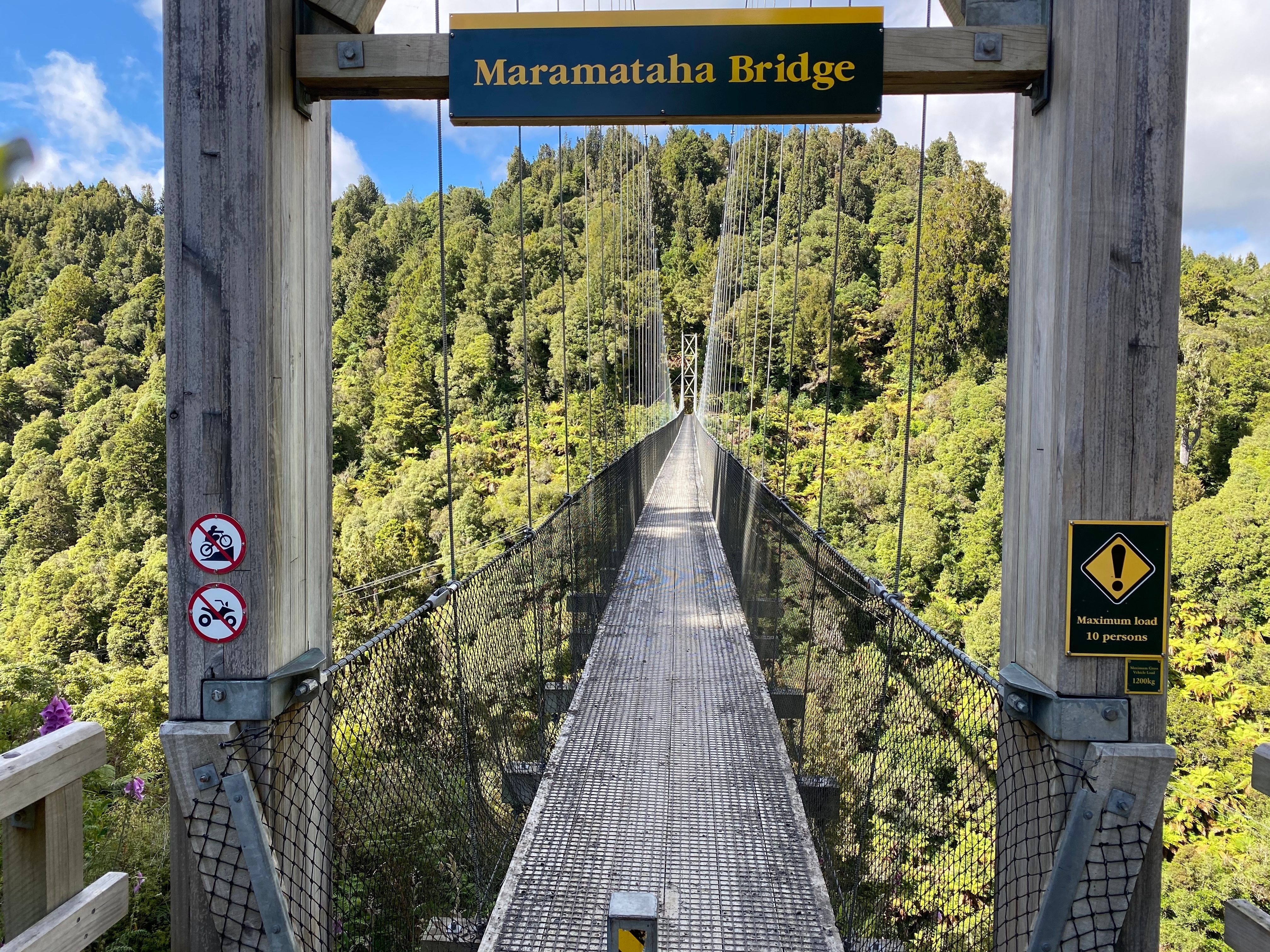

In 2010, the Department of Conservation began building an 84-kilometre-long cycle track through the reserve, which they completed in 2013.

The project included building 35 standard bridges and eight iconic swing bridges over Pureora Forest Park’s streams, rivers, and ravines. The trail traces the remains of historical logging tramways and takes in some of the park’s most dramatic scenery.

A conservation role model

New Zealand’s native forests face threats from multiple external influences. Introduced species like cats, rats, deer, and possums continue to upset their ecological balance, while trees still fall prey to illegal logging.

However, committed and ongoing conservation efforts in Pureora Forest Park are helping to minimise the damage in Pureora Forest Park. The park’s effective pest control has played an enormous part in preserving the park’s indigenous flora and fauna.

Today, Pureora is still one of the country’s most unspoiled and intact ecosystems, with wildlife to match.

Source references:

Timber Trail

Waikato Herald

Ruapehu

The New Zealand Herald

Sign up for the newsletter

By clicking on “Subscribe now” I will subscribe to the Conscious Explorer newsletter with all the information about mindful travel. Information on the success measurement included in the consent, the use of the shipping service provider MailChimp, logging of the registration and your rights of revocation can be found in our privacy policy.